OLD BOYS of the 10

Westville Old Boy Errol Stewart continues to add value

The schools I call the KZN10 have turned out many distinguished alumni and one of the alumna who surely ranks high among this grand group of gentlemen has to be Westville Boys’ High School’s Errol Stewart, who has recently been elected chairman of the board of governors at the iconic Durban Country Club, which celebrates its 100th birthday on 9 December, 2022.

If one were to write a P.G. Wodehouse-type schooldays novel, one could think of few better than Errol Stewart upon which to model one’s central character.

A gentleman’s gentleman, Errol has distinguished himself in a host of fields and endeavours and is a fine example of the principles that Westville Boys’ High School seeks to instil in its learners… resilience, respect, discipline, humility, character and dignity.

The wonderful pavilion on Bowdens… one of the many capital projects engineered by the Westville Foundation.

Among the many hats he wears, and has previously worn, Errol is one of the founding directors of the WBHS Foundation which, among its signature achievements, successfully engineered the establishment of the boarding house facilities at the school.

Apart from flying aeroplanes when he has a chance, the mind of this UKZN Law School graduate is no doubt well employed in his executive position at one of South Africa’s leading banks, as well as in the various other roles, both official and unofficial, in which he contributes add-value to society.

His academic prowess notwithstanding, this 1987 SA Schools rugby player and cricketer was also the recipient of WBHS honours awards in two other sports in which he gained provincial representative colours, namely hockey and athletics. Those schoolboy sporting achievements alone set Errol apart.

THE NEXT 50 DAYS… what a lot we got to look forward to…

Post-school, Errol played provincial cricket (wicketkeeper/batsman) and rugby (centre) for Natal as well as being capped for the Proteas, and has another rare distinction to his name – being a member of both the Natal cricket and rugby teams that were the respective Currie Cup champions of South Africa in 1995.

Oh, and not surprisingly Errol plays off a single-figure handicap when he gets time to launch his drive down the fairways of one of the world’s most renowned golf courses… at Durban Country Club.

A man of conviction, Errol retired from top-level cricket in 2003 (a 15-year first-class career) when, on principle, and in the face of much official pressure, he refused to accept the captaincy of the South Africa A team that was selected to tour a deeply troubled and divided Zimbabwe.

Bowdens… Home of the Griffin… and the scene of many an epic Westville first XV and first XI match…

The griffin is symbolic of WBHS… a mythical being that is part eagle and part lion, blessed with remarkable strength, unfailingly protective instincts and zero-tolerance for evil.

Errol Stewart… a man of many parts… a true WBHS Griffin.

Errol Stewart (2nd from left) with some noted Griffins of Westville. See who you can spot…

Sources: DCC, WBHS, CricInfo, News24

A resumption of the KZN10.com website and social media, as school sport returns – albeit without spectators – and Halfway Toyota Howick puts its support into assisting in keeping me alive. I urge you to join Brandon Brokensha and his exemplary motor vehicle dealership in backing me financially. I cannot do this alone. Contact me at joncookroy@gmail.com

When angry buffalo memories scatter your thoughts

It is amazing how you chance upon a random Facebook feed and find yourself spending a good couple of hours happily lost down Memory Lane.

Thanks Anthony Hall, your post sparked all sorts of happy reminiscences – although I must hasten to add an especially (unfond) uncomfortable afternoon memory too…

See if you recognise these players and the coach/manager etc. If so, please point out who is who amongst this quality group of KZN10 schoolboy cricketers from that early eighties era who as far as I can recall were outstanding as a team at that 1983 Nuffield Week.

A heartfelt thank you to Maritzburg College Old Boy and general manager of the outstanding Halfway Howick Toyota dealership, Brandon Brokensha, for being the first supporter of KZN10.com after the nightmare of the last 14 months. Please join Brandon and back me. I can be contacted at joncookroy@gmail.com

I do recall some of the guys almost immediately, although my facts and so on may be more than a little hazy here and there.

I notice the 1983 Maritzburg College and Natal Schools captain, the wicketkeeper/batsman Andrew Brown (front row, third from left); his school teammate, the left-arm seamer and right-hand bat Greg Walsh (back row, third from the right).

And on the far right in the front row, fellow Maritzburg College batsman Richard Delvin, who I think made 2 centuries at the 1983 Nuffield Week but missed out on SA Schools selection – there must have been some seriously in-form batsman at that Nuffield Week.

I think Greg Walsh, who was an outstanding fielder into the bargain, also hit a century at that Nuffield Week.

Not sure who took the bulk of the wickets.

Durban High School’s Robbie May (back row, fourth from the right) was an effective quick bowler so I am not surprised he is in this outstanding team, which I think (as I said) had a superb Nuffield Week.

I think that fifth from the left in the back row is Kearsney College paceman Anthony Hall, who made SA Schools that year as far as I can recall. Ant was seriously quick and uber-aggressive, and had the ability to cut the ball viciously off a reasonably responsive pitch.

Anthony Hall and his outstanding son James, the former Junior Springbok scrumhalf whose skill at Stade Francais is making serious waves in French Top 14 Rugby. Ant and James are two of Kearsney College’s finest. I am pleased, too, that Ant’s dad went to Maritzburg College.

I was last at school in 1982 and as I type this I vividly recall facing Ant’s right-arm pace and fire – a charging buffalo had nothing on a suitably riled-up Ant Hall – from one end on Kearsney’s splendid AH Smith Oval while the ultra-talented Natal Schools (and further) flyhalf Cameron Oliver (RIP), who was a left-arm quick capable of weaving red-ball magic when the mood took him, was at full-throttle from the other end.

Just to get bat on ball – at all – on that testing fourth term 1982 Saturday afternoon felt like a triumph in itself.

I think that second from the right in the back row is Michaelhouse’s hard-hitting all-rounder Dave Burger, who later finished his schooling at Maritzburg College.

I think that’s Beachwood’s Craig Small in the front row – while I think Craig Beart of Hilton is there as well, alongside Rich Delvin. And the teacher coach in the front row has to be Hilton’s Ant Lovell.

And Dean van der Walt of DHS is there, it might have been Dean’s second year in the side.

Help me out guys.

When the ticks on a ruffled buffalo are biting in all the wrong places it’s no place to be.

Maritzburg College Old Boy Ryan Moon off to top-flight Swedish soccer club

In breaking news, Maritzburg College product Ryan Moon has landed a three-year contract with Swedish premier league club Varberg Bols FC.

The 25-year-old Moon, who is from Woodlands in Pietermaritzburg, leaves his current club Stellenbosch FC and is due to fly out on Thursday. The Sweden premier league, or Allvenskan, kicks off the new season next weekend.

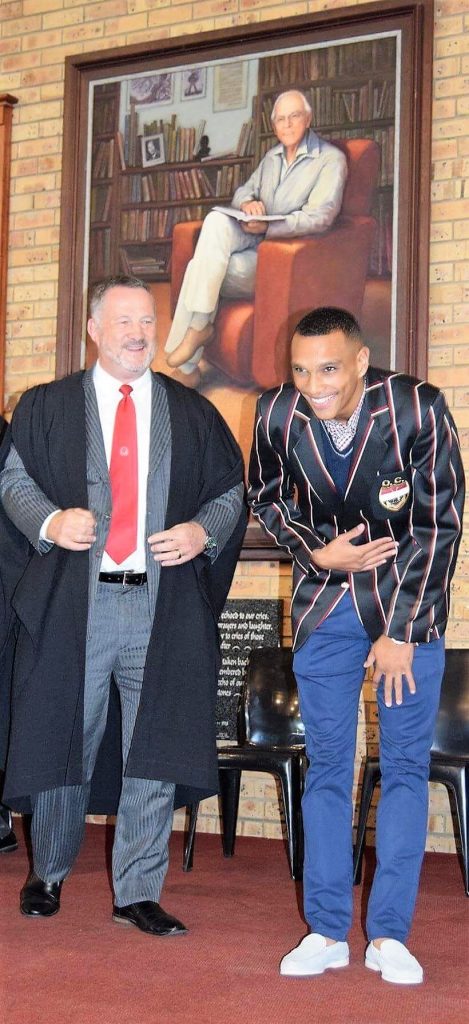

Feature photo: Ryan is presented with a Maritzburg College Old Boys blazer by headmaster Chris Luman at a function in the school’s Alan Paton Hall in mid-2018.

Apart from his distinguished years at Maritzburg College, where he excelled in the Red, Black and White colours, Moon also learnt his trade at the Woodland and Pirates soccer clubs in Pietermaritzburg before making his debut for his local SA premier league club Maritzburg United in 2015.

Hardly a year later his exploits earned a move to traditional SA soccer giants Kaizer Chiefs.

In another local tie-up, Moon’s representative is fellow Maritzburg College Old Boy, the 29-year-old Gauteng-based attorney Modise Sefume, of Giyose Sefume Attorneys, who revealed to News24 today that negotiations have been ongoing in a bid for Ryan to realise his overseas dream.

Modise Sefume during his schooldays at Maritzburg College.

“We’ve been working on it a couple of months now,” said Modise. “The guy is excited, it is a big opportunity and he really wants to get there, get going and prove himself.”

Ryan leaves with the blessing of Stellenbosch FC and his immediate goal will be to break into the Varbergs starting line-up and help his new club to improve on last year’s 11th-place finish in Sweden’s premier division.

Ryan’s older brother Bryce has, like his younger brother, also played for Bafana Bafana. Their dad, Patrick, was also a prominent footballer.

Read more about Ryan in this earlier KZN10.com article

https://kzn10.com/maritzburg-college-old-boy-soccer-star-ryan-moon-on-pmb-fa-cup/

Maritzburg College Old Boy and Bafana Bafana striker Ryan Moon, seen here presenting his Kaizer Chiefs shirt to headmaster Chris Luman in mid-2018.

From flyswatter to R470 million: Hilton & Maritzburg College Old Boys’ massive success

A Maritzburg College Old Boy (MCOB, Class of 1992) and Hilton College Old Boy (’98) have taken a business concept that began in the lounge in 2006 to an approximate R470 million cash sale as of yesterday.

Mr Price is the buyer, while the 2 founders, MCOB Shane Dryden and Old Hiltonian Andrew Smith, along with a second Hilton College Old Boy, Smith’s 1998 Hilton classmate and head boy Paul Galatis, are the three primary beneficiaries, their being the 3 directors of Yuppiechef, the hugely popular Online kitchen and homeware retailer.

Dryden and Smith along with their Yuppiechef management team, will continue to operate the business for Mr Price.

Hilton College Old Boy (Class of 1998) Andrew Smith.

Smith, who received the highest academic marks in his matric class year at Hilton, and Maritzburg College Old Boy Dryden are the 2006 founders of Yuppiechef, while the third and only other director is Galatis, who joined in 2008 and brought design skills and e-commerce marketing knowledge to complete the Yuppiechef recipe.

The concept of selling kitchen and household goods Online that began in that Plumstead, Cape Town lounge 14 years ago has almost taken on a life of its own. A fly swatter gadget, that was bought by Andrew’s mum, was their first product and first sale.

Flags and handy kitchen implements then became 32 e-commerce kitchen products, 11 sales were made in the first 4 months (10 to family and friends), and after 12 months the sum total of huge endeavour and smart work was only 200 customers.

Maritzburg College Old Boy (Class of 1992) Shane Dryden.

It took 5 years before they could actually pay themselves a salary. E-commerce was the only way to go as they did not have capital. They could only order more stock once they had been paid for what they had sold.

Dryden is the natural foodie among the trio, always having had an interest in the subject, and of one Sunday morning he came up with the name “Yuppiechef”.

All in all, a fantastic achievement for these Old Boys of Hilton and Maritzburg College. A KZN10.com congrats to Shane, Andrew and Paul.

Hilton College head boy in 1998 Paul Galatis.

Yesterday, Yuppiechef said on their website, “We’re still going to be the same Yuppiechef in name and people and the way we work. Our co-founders, Andrew and Shane, will still be leading us, and we’ll have our same teams and managers firmly in place.

“Some of us have been around for a long time, helping craft the company that Yuppiechef has become, and some of us are privileged to have come more recently to work for a brand that customers have shown so much love to over the past 14 years. We all take our responsibilities seriously, and are committed to making Yuppiechef the best that it can be.

“If you’re one of our customers already, thank you for your support so far, and if you’re not, we’ll keep on trying to win you over.

“There’s a lot more good stuff coming!”

It is good to remember… schoolboy rugby

Following my interesting little story yesterday…… https://kzn10.com/two-remarkable-school-sports-records/

…… I have just recalled another slice of nice stuff that I think you could find interesting:

IF… my memory is correct… An interesting fact is that since the beginning (not sure the year) of Natal Schools’ Craven Week rugby selections, Maritzburg College lead the way as far as most Nat Schools caps (players selected) is concerned, then Glenwood then Michaelhouse.

Michaelhouse featuring in third place is a noteworthy achievement when one considers the relatively small intake of boys compared to the bigger schools.

That 1984 to 1987 Michaelhouse first XV era was an interesting one. Serious talent and the ability to respond well to adversity (the illness-plagued 86 side deserves special mention).

Guys like the multi-talented Victor Anderson, his scrumhalf James Wilson, big Bob Mitchell, 85 captain Wayne Witherspoon, Richard Firth, 86 captain Bruce Herbert, lock/loosie Will Hardie, flyhalf Murray Gilson, 9 Murray Collins, Ross Armstrong, gifted athlete Mike Jeffery, flyhalf Mark Olivier, the versatile loosie/midfielder James Arnott, etc etc

It is good to remember, in that there is much to learn.

So near yet so far… let’s hope we’re not too far off from it happening again

Around end-September 2020 would have seen the 61st edition of Maritzburg College’s stellar Oppenheimer Michaelmas Cricket Week… but it was not to be. These annual four days of cricket, glorious schoolboy first XI cricket, have been etched into my sporting heart for so long it felt almost like a bereavement at the time.

Feature photo: Some of the Oppenheimer Michaelmas Cricket Week’s most distinguished alumni. See how many you can identify and then attach them to their schools.

Yes, there are far more important things in life, yet at the same time one must not minimise the impact of the special things that make the trials and tribulations of life (almost) bearable.

As a reminder of what we have taken for granted – until last year- here is a look at the KZN10.com first XI line-ups that represented our province’s premier cricket schools at the 2017 OMCW.

My rather battered front cover of the commemorative 58th annual Oppenheimer Michaelmas Cricket Week programme.

Let’s not worry about scores etc. Let’s just reflect on names and the personal and collective cricket memories they conjure up.

Maybe you’d like to share some of them?

2017 KZN first XI’s at the 58th Oppenhemer Michaelmas Cricket Week

Hosts Maritzburg College first XI

Scott Steenkamp (capt), Damian Walden, Brad Sherwood, Matt Crampton, Michael Horan, Brynley Noble, Andre Bradford, Jayden Gengan, Cameron Holloway, Jared Campbell, Dean Dyer, Keagan Collyer. Staff: Dave and Elmarie Pryke

Clifton College first XI

William Masojada (capt?), Scott Quinn, Matthew Montgomery, Joshua Brown, Luke Shave, Simon Holmes, Ariq Chetty, Daniel Freitag, Daniel Elgar, Connor Veitch, Jason Groves, Muhammad Noorbhai, James Feuilharde. Staff: Matt Savage, Yash Ebrahim, Oliver Cash

Kearsney College first XI

Blaise Carmichael, Patrick McGrath, Rory Bloy, Luke de Vlieg (capt), Robbie Koenig, Steven Conway, Michael Brokensha, Marco Gouviea, Carl Heunis, Jared Brien, Jethro Strydom, Bradley Beaumont. Staff: Hubert von Ellewee, Jonathan Beaumont

Back cover of the programme… unfortunately a little tattered it has become among my many books and assorted memorabilia

Michaelhouse first XI

Sean Gilson (capt), Tom Price, William Glassock, William Norton, Thomas Trotter, Fraser Jones, Nathan Wesson, Michael Brownlee, Liam England, Declan Newton, Gift Mokoena, Cameron Leer, Michael Meneer. Staff: Dean Forword, Jason Wulfsohn

Northwood first XI

Slater Capell (capt?), Ali Hamid, Jordan Edy, Andile Mogagane, Daniel Zvidzui, Alvin Chiradza, Samkelo Gasa, Wander Mtolo, Jeremy Martins, Mpumelelo Xulu, Luke Stevens, Cameron Ciaglia, Nicolas Deeb. Staff: Divan van Wyk, Riaan Minnie

Hilton College first XI

Robbie McGaw, James Ritchie, Michael Sclanders, Gareth Schreuder, Chris Meyer, Brandon McMullen (capt), Michael Booth, Alistair Frost, Jared Venter, Alex Roy, Mike Frost, Kamogelo Selane, William Haynes. Staff: Dale Benkenstein, Sean Carlisle

DHS first XI

Safwaan Barradeen, Kribashan Naidoo, Liam Green, Martin Mugoni, Sumiran Ramlakkan, Jordan Bryan, Joshua Stride (capt?), Brayden Sambhu, Sinolin Pather, Taine Owen, Tawanda Zimhindo, Rodney Mapfudza. Staff: Oss Gcilitshana, Florian Genade

The 2017 Hilton College first XI captain Brandon McMullen seen here post-school in the UK.

Glenwood first XI

Daelen Fynn (capt?), Jared Paul, Thamsanqa Khumalo, Cameron Reid, Caleb Alexander, Joe Jonas, Nikhil Prem, Hayden Rossouw, Alex Pillay, Khwezi Gumede, Jaden Hendrikse, Nathan Archibald. Staff: Jarryd Chetty, Brandon Scullard, Bevon Futter

Westville first XI

Carl Jairaj (capt), Matthew Pollard, Sam Gervasoni, Josh Brady, Josh Parker, Caleb Pillay, Brandon McCabe, Hayden Bowman, Jaryd Cook, Bonga Chepkonga, Keshlan Govender, Jandre Viljoen, Mazwi Meyiwa, Jarred Oosthuizen. Staff: Fabian Lazarus, Thomas Jackson, Chester Comins

* Not sure if all the captains are correct. Please advise. Thanks

Westville is in Director of Sport Waylon Murray’s heart

29 June 2020 – Sport has played a defining role in the life of Waylon Murray. As a schoolboy, it led him to Westville Boys’ High (WBHS), then on to a professional rugby career, during which he wore the green and gold of the Springboks, and then, more recently, it led him back to WBHS.

In his primary school days, he attended Berea West where he initially excelled at cricket and athletics. “I really enjoyed my time there and I had a lot of positive people steering me in the right direction, especially with regards to sport,” he said in a recent chat with KZN10.com’s Brad Morgan at WBHS.

His mother did not want Waylon playing contact sports, but an approach by the Principal Philippe Paillard led to her consenting to Waylon playing rugby in grade 5. He ran out at eighth-man but, he admitted, he was undersized.

“Even when I got into high school, I was tiny in comparison,” he reckoned. “I had a growth spurt in the middle of grade 9 and into grade 10. I was also a year younger than most of my classmates. I finished school at 17.”

When it comes to planning your next school sports tour look no further than former Hilton College first XI captain Craig Goodenough who’s been there, seen the movie and bought the T-shirt factory.

Waylon’s move to high school also coincided with a move to the backline due to his speed and footwork. “I enjoyed tackling, so I gravitated towards centre. It was close to the action. I started in the pack and then ran away from it when I got into high school,” he said with a laugh.

Although many of his classmates made the move to Westville, for a long time Waylon had no idea what lay in store for him regarding a secondary school destination. He explained: “At that time, I didn’t come from a privileged background. Philippe Paillard suggested, with the help of a few teachers, that I apply for a scholarship. I didn’t know where I was going to be. I was very fortunate that sport gave me an opportunity at Westville.”

As the son of a single mother, he would not have had an opportunity to attend Westville without that scholarship, Waylon said. “Nestor Pierides and Trevor Hall decided to take a chance on me and I came to the school.”

Initially, it took him a little time to adjust to Westville because he was, in his own words, “very introverted”, but he felt protected because of the support of Nestor and Trevor. “They were very supportive and they gave me a lot of opportunities to excel at school. My mom lent on the school a number of times when she couldn’t manage and every time they helped and were there for me.

Hill Premium Quality Cricket Balls stay the distance. www.hillcricketballs.co.za

“Being involved in team sport, even though I was socially awkward to a degree (in grade eight, I was still trying to figure out who I was), I was very grateful that I played with many good leaders and good people. It was helpful that I could play sport, coming in as a small fish into a big pond.”

Westville has a well-earned reputation for academic excellence and that, fortunately, was not a difficult transition for Waylon. He explained: “I have always been a disciplined person…and I assumed the role of head of the household (at least in my head) because my mom was a single parent.

“I always carried that weight of expectation with me. Whatever I did when I was at school, I was incredibly disciplined, which helped me in my [rugby] career. Obviously you need talent, but I wasn’t the most talented rugby player to ever have a professional career, but I did know how to be a professional and work hard. That helped me jump start my career.”

Sport helped Waylon integrate into life at Westville and he excelled in many different sports, playing for the 1st football team for three years, the 1st cricket side for three years, the first rugby team for three-and-a-half years [before the introduction of Bok Smart, which nowadays would have prevented that happening]. He also shone in athletics: in hurdles, long jump and the triple jump.

In 2018, Waylon presented his Springbok blazer to Headmaster Trevor Hall. The blazer now resides in the WBHS Griffin Room. (Photo: https://www.facebook.com/westvilleboyshighschool/ Westville Boys’ High on Facebook)

He named Doc Cowie as being a big influence on his cricket. Waylon was an opening bowler and middle order batsman who in matric played with future Dolphins’ batsman Martin Bekker and future Dolphins’ all-rounder Robbie Frylinck, who would go on to play T20 cricket for South Africa.

“I used to bat a lot in the middle order with Robbie Frylinck. He’s obviously matured and got a lot better after school,” he smiled. “I remember a lot of innings where we batted together, and we also bowled together, of course.”

In his matric year, when he was also the Head of School, he found that he had lost some of his love for cricket because of the long hours it demanded of its players. He started to turn his focus towards rugby. “I thought that was maybe a sign that I needed to concentrate more on rugby, even though I continued to play first team cricket. In football, I was never amazing, but because I was good at most sports I could manage to some degree.”

He added: “I enjoyed playing different sports. Looking back on it now, I am very grateful that I knew every season Nestor would come to me and say what he needed me to do. It was quite refreshing; after a long rugby season you look forward to football, and after football you look forward to cricket.”

In matric, though, there was disappointment when he missed out on selection for the KZN Schools rugby team. “I had a good year, but I was a bit young at only 16-and-a-half,” Waylon said.

The Westville 1st XV of 2003 included Waylon Murray as captain and Njabulo “Jabz” Zulu, his centre partner, who today coaches the Westville 1st XV with Jeremy McLaren.

“The Sharks at that time expressed an interest in me and they wanted me to do post-matric. I came back and fortunately I made the Craven Week team. I wasn’t on the radar for SA Schools or anything like that. But I played all the Craven Week games. We had a really talented team.”

The KZN line-up included Alastair Hargreaves (DHS), who captained SA Schools, future England international Brad Barritt (Kearsney), who also made the SA Schools side, and Westville’s Chris Micklewood (who would make SA Schools the following year) and Njabulo Zulu, among others. Zulu, Waylon’s partner at centre for Westville, is now coach of the Westville 1st XV with Jeremy McLaren.

Throughout his high school career, Waylon had paired with Brad Barritt when turning out for Pinetown and Districts. Missing out on the Craven Week team in 2003 was a big blow, but reuniting the following year was an enjoyable experience, he said: “It was good to be back with him that year and to finally get what I felt was recognition for my talent at the time.”

He joined the Sharks Academy in his first year out of school, but was in for a nasty shock when he didn’t crack the nod for the College Rovers under-20 side. But that proved to be fortuitous.

Attention to detail separates the best from the rest. Talk to the experts. http://www.hilliarandgray.co.za/contact/

“Someone approached me at the Union and said there was an opportunity for me to go to Jaguars and play in the Premier Division, so I would jump a few levels. He felt I had been overlooked.”

It proved to be a fantastic move for Waylon. At Jaguars, he joined up with players, many of them from the Sharks Academy, who were part of the development programme.

“It became one of the best teams in the Division at that time,” he said. “JP Pietersen was in that side, Dusty Noble ended up playing for the Sharks, Howard Noble played Springboks Sevens, so we were a bunch of misfits in a sense and we landed at Jaguars. We just exploded. We were beating teams with a really young side. Most of us were under-20, under-21.”

Dick Muir was coach of the Sharks at that time and re-introduced club trials which, again, proved to be to Waylon’s benefit.

“Dick Muir had three rounds of trials. The Sharks players could watch. At the final trials, if you were chosen (I think there were 30 players), you then had a chance to have trials against the Sharks.

“Dusty, JP and I ended up making it all the way through. From not making College Rovers, to going to Jaguars, to going to Currie Cup trials and being chosen for the Currie Cup squad that first year was an incredible, fairy tale start for me.”

Check out the Cell C personal and business contracts at https://www.cellc.co.za/cellc/contracts

It was a remarkable elevation in a very short time and it was mind-blowing for the young centre. “I was star-struck. I was a year out of school and suddenly playing with these professionals I looked up to,” Waylon said. “But I was very fortunate that the Sharks had a very experienced group of leaders at the time. A lot of youth was injected, so there was a really nice mix.

“John Smit, AJ Venter, Percy Mongomery, all these guys that were in that group did so much for the development of the young guys. It was a really nice culture. You weren’t afraid to fail. It was a good place to be. We went on to have a good season a year after.”

His debut for the Sharks came against Griquas at King’s Park. In a game he doesn’t remember too clearly, one incident stood out: “I remember chasing through a kick and thinking I was about to score a try and Henno Mentz came in and got there before me,” he said with a rueful grin. “It’s all these weird memories. The pace of the game meant there was no let-up. For me, the whole game was over in a flash.”

Waylon had started studies in marketing when he joined the Sharks Academy, but his rapid ascent to the senior team soon put them on hold. In retrospect, he said, that was a good thing as marketing was not something he was interested in at all.

A screenshot taken from a YouTube conversation, dated 25 April 2020, between Waylon Murray and Jabz Zulu during the Covid-19 lockdown (Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h9HxFTxaywQ)

By 2007, Waylon was in the Springbok reckoning and when Jake White opted to rest his frontline players ahead of the Rugby World Cup, Waylon got to pull on the famous green and gold jersey during the Tri-Nations.

Then, when Jean de Villiers was injured in the first game of the World Cup, it appeared that he was in line for a call-up to the biggest tournament of them all. Jake White, though, had other plans and opted for Wayne Julies, a player he was more familiar with, but one who had played little rugby for the Bulls that season. It hurt, Waylon admitted.

Nonetheless, during that season he got to spend valuable time with a very experienced Springbok squad. “I absolutely enjoyed being a part of the set-up,” Waylon said. “That Springbok team was really special in terms of talent. They knew how to win and they were a different breed.

“I stayed with them for a couple of months, even in the games I wasn’t playing, as part of the tour party. That was enjoyable. I got to spend time with incredible players, some of the best to ever grace the game.”

When the match is tight and every run counts, you can count of Clox Scoreboards of KZN. http://clox.co.za/

In 2007, Waylon also helped the Sharks top the Super Rugby table. They then downed the Blues 34-18 in the semi-finals at King’s Park to secure a home final against the Bulls. In a thrilling back-and-forth showdown, the Sharks were pipped 20-19 in the dying moments of the title-decider after a Bryan Habana try which had resulted after a disputed steal in the loose by Pedrie Wannenberg. It is the closest the Sharks have yet come to lifting the Super Rugby title.

As a young player making his mark, considerations of playing elsewhere were not at the forefront of his thinking but, after a very good run of over five years with the Sharks, Waylon found himself with a crucial decision to make when the Lions made an approach for his services.

“I think it is a crossroads for every professional rugby career,” he said. “You mature with the game and you learn to have honest introspection with yourself, including when it is the right time to go. I remember at the time the Sharks still wanted me to stay, but I had had a couple of injuries. I went to the Lions.

“It was a hard decision to leave, but I was probably going to get more opportunity with them. It was difficult leaving my safety net. As a competitive person, you want to prove people wrong and show you can come back from injury, even stronger. There was unfinished business. Going to the Lions felt like a fresh start.”

The transition was difficult in the beginning, and Waylon questioned himself, asking why he had made the move. But those misgivings disappeared. “When you push through an uncomfortable space and just stay and hang on, you get the reward,” he said. “That was the case with Joburg. I absolutely loved it. I loved playing for John Mitchell. It was nice to get the full backing of a coach.”

Mitchell has earned a reputation as a tough coach, but it was his straight-forward nature that appealed to Waylon and he took lessons from that approach. He explained: “John didn’t skirt around honest conversations and I enjoyed that. That’s how I have tried to maintain my relationships afterwards with coaches. You tell me exactly what you are thinking, rather than let me assume what it is. To have those hard confrontational talks, especially in pro sports, can be difficult. But I would much rather have that honest feedback.”

Towards the end of his time with the Lions, Waylon underwent a knee operation, which ultimately led to him leaving the union and signing with the then Southern Kings. Injuries, he said, are something every player has to deal with through the course of a season.

Take a 5-star break from life in the fast lane. Contact Fordoun CEO and former Michaelhouse rugby star Richard Bates for your well-earned break. https://www.fordoun.com/

“I think every rugby player, to a certain degree, never comes into a match fresh, even if they are injury-free. You are always carrying some sort of knock. It’s about trying to get through the season and staying as fresh as possible, which is, I suppose, the nature of the game. Injuries are tough [to deal with], especially when you get a bit of momentum. I was hurt at different times when I had built up momentum.”

Recalling the first time he had to deal with a serious injury as a professional player, he said it was challenging, but also a time of growth: “The first time around, it is quite a dark place to be. You can’t see the finish line and you are forced to focus day in and day out on what you are doing. It’s quite tough to find motivation. In that time, I learnt to find some inner resilience, in terms of being more professional and setting new goals, smaller goals, and managing them.

The Southern Kings’ experience was memorable, he said, because of the people of Port Elizabeth and how they wholeheartedly supported the team.

The next five years were somewhat nomadic as he turned out for the Bulls, the Sharks again, and the Kings after that. In 2016, he tied the knot, marrying Nicci Goodwin in a wedding that was shared on Top Billing. Then, in 2017, he moved abroad to join the French Fédérale 1 club Mâcon. It proved to be a pivotal decision in Waylon’s life.

Waylon’s wedding to Nicci in Durban was a stylish affair which was featured on Top Billing.

Recalling that time, he said: “I went to France. My son Grayson was born there. It was an incredibly difficult time, but I loved France. I was there for 16 months, not very long. I should have gone earlier. I was with Mâcon, so I was close to Lyon. It was always a dream of mine to get overseas. I was not playing in the top division, but it was still a chance to travel.

“That season put a lot of things into perspective. I didn’t feel a pressure not to achieve – I was always professional and I worked hard, no matter where I went – but understanding where I was in my life, what I wanted next, and what I wanted for my family became clearer and the decision became a lot easier as the season went on. I could have milked another one or two seasons, but I thought it was time to have a little bit more stability.” The question became what form would that stability take?

“I had spoken to [Westville Headmaster] Trevor Hall throughout my entire career,” Waylon said. “I had reached out to him when I first got to France and asked how things were going at the school. We started to talk a little bit more and he told me that if I wanted to come back he would create an opportunity for me, which would give me a chance to give back to the boys through my experiences.

“At the time it wasn’t at the forefront of my thinking, but near the end of the season, after my son was born, I wanted to start afresh and try something different, and put my mark on a different project.” The move to Westville was agreed upon.

Waylon with Guy Coombe, who coached the 2003 Westville 1st XV that also featured Jabz Zulu, and senior sports officer Thomas Jackson. (Photo: https://www.facebook.com/westvilleboyshighschool/ Westville Boys’ High on Facebook)

When he arrived at the school, Waylon was tasked with guiding, counselling and supporting high-performance players across all sports. But the position of Sports Director was soon to become available.

He explained: “When I came here, Sharmin Naidoo was the Director of Sport, but he was in the process of leaving. I had the opportunity to start something different with the Sports Department. Sharmin was here for 10 years and he did incredible work, but I wanted to do things in a different way.

“I wanted to educate and help the kids to understand that sport is great and we would like [some of them] to have professional careers, but what is more important is your contribution to the world and how well-rounded you are when you come out of the school. It is about managing expectations and trying to create good individuals that are going to return to our legacy when they leave school.

“If they make it as professional sportsman, so be it. For me, what keeps professional sports going are the kids that continue to play after school, including socially. That’s why I always encourage kids that if it is their passion, in rugby, for example, but you’re not making it professionally, just play because you love it. There is a shelf life to your sporting time and you won’t have those gifts forever.”

“Megaprop prides itself in offering a WHOLE OF MARKET solution to your property investing in the United Kingdom.” With over 30 years’ experience in the SA and UK property markets Maritzburg College Old Boy and well-known former wicketkeeper/batsman & hockey striker Arthur Wormington is your go-to man. Contact Arthur

It is important, too, that boys should enjoy the process of learning and growing together and not just focus on fixtures and results, he added. “I tell kids they always think about their big match on the weekend, but the actual room for growth is in the week.

“I recently spoke with Brad Mooar, who is an assistant coach with the Crusaders, and he was a really good mentor for me, because he was with the Kings before he went to the Crusaders, and he always used to tell me not to worry about the weekend, the week is where you have fun and grow. The matches are extra. As soon as you look too far ahead you stumble.”

Returning to Westville has been an enjoyable experience, Waylon said: “It is a very supportive environment and I think that’s always what makes Westville unique. It’s a really comfortable place where you feel you can be yourself.

“For me, it’s that mind-set of being of service to others, so I felt when I got here there were so many people that wanted to help. I am the type of leader that doesn’t want to have all the answers. I want to lead and grow with people. You learn from others and you get ideas from them.

“I am really grateful to be able to come into a place where I can be creative and try to do something special in a school that has changed, but which has maintained the foundations it was built upon.

“For me, it’s kind of a fairy tale [to return to Westville] because during my rugby career it was tough going contract to contract and moving to new places. Now, I have come to a place where I can finally breathe and relax, where I don’t have to worry about getting up and performing. It’s a different type of pressure. Being in this environment is very conducive for growth.”

Back in the Westville colours and loving his job as Director of Sport, Waylon Murray.

Casting an eye to the present day, 2020 looked poised to be a memorable year for Westville sport, especially the winter sports of rugby and hockey. The rugby team was expected to be one the school’s best teams yet, while the hockey side was coming off an undefeated 2019. But then Covid-19 flipped school sport and the world on its head.

Reflecting on what Westville and the school’s leading sportsmen have missed out on, Waylon said it would have been great to have outstanding teams, but the focus has switched to helping the boys deal with the disappointment of missing out on their season: “We’ve tried to be in constant conversation with the boys in terms of what they’re thinking and how they’re feeling and not concentrating on the loss, because that is what it feels like.

“Expectations were high and they wanted an unbeaten season, but it is sport. We hoped the season would turn out that way. We don’t know now and will never know [how it would have turned out]. We know who we are and we understand the boys are most important to us.”

Get a firmer grip on your possessions with KZN’s Titan Technologies. https://www.titantech.co.za/

He expects them to deal with the setback well, he added, saying character and resilience define the Westville boy.

“We’ve got a great leadership group under Gavin Sweet, who does our leadership,” he added. “I work closely with Gavin and share a lot of ideas. We do a lot of videocasts, interviewing people, so we are really like-minded in that sense. We definitely support each other when we are dealing with an issue. That culture of collaboration is vital. We grow as people, so leadership and emotional intelligence are important.”

Concluding, he said: “It’s been incredible coming back to see what has happened at Westville, the successes the school has had, the good years and the bad years. There has definitely been a shift since I was in school, with Westville continuing to rise and excelling in sport and academics.

“We always say sport is a good outlet for the boys, but academics is their primary focus. They need to understand that.” And those words, coming from a former professional sportsman and the school’s Director of Sport, are sage and pleasing words indeed.

It is imperative for coaches to know what works for you. Get in the driving seat with the tried and tested. Contact Trish right now at info@trishsutton.co.za

Top waterpolo player, top cricket coach, and now CEO of the DHS Foundation

15 June 2020 – Andrew Shedlock, as the CEO of the DHS Foundation, is a well-known figure at Durban High School and in the school’s community. Before taking up his position in 2019, he enjoyed a successful career as an international waterpolo player before turning to cricket and making his mark as a coach on professional and schools’ level players alike.

As a young boy at DPHS, he excelled as a swimmer and represented Natal Schools in the pool in 1973 and 1974. He also had aspirations of success on the cricket field.

When it came time for high school, he moved to DHS where he continued swimming and playing cricket, which was a challenge at times. In a recent interview, he said: “In those days the swimming galas used to take place on a Saturday morning, so I, on the odd occasion, would go to a gala and swim (I was the number one swimmer in my age group), and from the gala I used to go to cricket matches. That happened in second form (grade 8) and third form (grade 9). In third form, I swam for Natal Schools.”

The following year, he was appointed captain of the DHS under-15 A cricket team, but then something occurred that was to have a huge impact on his life. He went to watch his brother playing a waterpolo match and when his brother’s team found themselves short of a player they asked Andrew to play. He did.

“Being swimming fit, it was fine. I jumped in the pool and I enjoyed the game and I said ‘this is me’. I had one or two cricket games left and I said ‘at the end of this I am giving up cricket’. I went and finished my cricket games.”

As the return of summer sports approached after winter, he started swimming again and told the waterpolo coach he wanted to play waterpolo. He was then selected for a Stayers tour of the Eastern Cape.

When the match is tight and every run counts, you can count of Clox Scoreboards of KZN. http://clox.co.za/

“Now, everything was flying and I was training and I understood that I was giving up cricket. The last week prior to the tour I was called into the Headmaster’s office, who was then the legendary Des ‘Spike’ Thompson.

“He turned around to me – and every time I go into that office now I have these visions of standing there in front of him – and from where I stood you could see the whole school from the windows, and he said to me ‘Shedlock, you are not allowed to give up cricket. The major sports at this school are cricket and rugby. They take preference and I am not allowing you to play waterpolo. I want you to go from office to the cricket practice (because I was captaining the under-15 A team at the time) and that is it! Don’t ask questions.

“I said, ‘but sir, I don’t have my cricket kit with me’. He said, ‘that’s fine. You go to waterpolo today. But when you come back in the fourth term, I expect you to play cricket’. I went from there to the waterpolo practice and went on the waterpolo tour. Then, when I came back in the fourth term, I said to the waterpolo coach, Mr Nico Lamprecht, ‘What must I do?’ and he told me to go to waterpolo.

“I played first team in the fourth form, which in those days was unheard of. I was still under-15. I went on and played SA Schools in 1980 and I captained SA Schools in 1981. I never looked back.

Andrew captained the South African Schools waterpolo team of 1981.

“One day I asked Nico what happened with my situation at DHS. He said he went to the Headmaster after the tour and said to him, ‘Mr Thompson, what takes preference, first team waterpolo or under-15 A cricket?’, so Spike told him it was obviously first team waterpolo. Nico said ‘Shedlock’s in the first team’. That’s how he got around me being able to give up cricket.

“Funnily enough, I became the reference, not only for DHS, but also for other schools. When guys wanted to give up, they would point to Shedlock at DHS, who was able to do it. People after that used me as an example.”

Andrew Shedlock and Steve la Marque proudly display their SA Schools’ colours.

After school, Andrew went to Stellenbosch University. As part of his degree, he did a level two cricket coaching course. Later, when he returned to Durban, he did a level three course.

During his time at Stellenbosch, in 1986, he also represented the South African men’s waterpolo team. In 1989, he completed his studies, having qualified as a biokineticists. He needed to do an internship and, fortuitously, the man he did it under was Richard Turnbull. Turnbull had earned himself a highly respected reputation and, as a result of that, was involved with both the Natal cricket and rugby teams.

While at university, Andrew was selected for the South African men’s waterpolo team in 1986.

Andrew, who was living in Durban, drove up to Pietermaritzburg every day to work with Turnbull, who, besides running a successful gym, Body Dynamics, where a number of other biokineticists were doing their internships, also worked in the Sports Office at the local university. Future international cricket coach Graham Ford worked there too. When Turnbull decided to set up a Body Dynamics Gym in Durban at Collegians Club, he chose Andrew to run it.

Back in Durban, cricket again entered Andrew’s life. “I got involved with the Natal cricket side. In those days, Mike Procter was the coach. Kim Hughes was the captain. There were guys like Peter Rawson, Neville Daniels, and Rob Bentley. I became friendly with Kim, and the Aussies were probably a bit more advanced than us in those days [in how they utilised sports science]. Fitness was quite a thing for him, so he used to come into the gym quite often and encouraged all the other guys to come.

When it comes to planning your next school sports tour look no further than former Hilton College first XI captain Craig Goodenough who’s been there, seen the movie and bought the T-shirt factory.

“In 1990, Richard [Turnbull] worked closely with Ian MacIntosh and the Natal rugby side (which was, of course, the first year that Natal won the Currie Cup). Because Richard couldn’t come to Durban that often, I used to deal with a lot of the rehabilitation of the players. That year I rehabbed Dick Muir when he injured a hamstring, Jeremy Thomson popped a shoulder, and Wahl Bartmann was another player I worked with. I did the rehab for a lot of those Natal players. Biokinetics in those days wasn’t a recognised profession. It was really, really tough.

At that time, too, Andrew was still playing top level waterpolo. In fact, the next South African national team to tour internationally after the ground-breaking cricket tour of India in 1992 was the waterpolo side and it was not a gentle introduction.

“We went to a pre-Olympic waterpolo tournament in 1992 in Hungary and played against Hungary, the USA, the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia and Italy [who would go on to claim Olympic gold],” Andrew recalled. “We played against all the teams that were two months out from the Olympic Games, so they were peaking and those were their Olympic sides.”

Six members of the Natal waterpolo team of 1992 were selected for the national team, including Andrew Shedlock.

By then, Andrew had also moved to the Health and Racquet Club in La Lucia. Then, Graham Ford took over from Mike Procter as Natal cricket coach.

“Because of his association with Richard at Maritzburg University, Graham wanted Richard to work with him,” Andrew said. “But Richard couldn’t because, being in Maritzburg, he couldn’t get down to Durban all the time. So I went and helped. I used to go to practices and warm-ups for games.

“On Saturdays and Sundays, during a four-day game in Durban, I would be there and act as a fitness assistant. There were players like the legendary Malcolm Marshall, Clive Rice, Peter Rawson, and then our local talent which included Andrew Hudson, Jonty Rhodes, Lance Klusener, Shaun Pollock, Errol Stewart, Neil Johnson, Dale Benkenstein, Mark Bruyns and Doug Watson.

Check out the Cell C personal and business contracts at https://www.cellc.co.za/cellc/contracts

Being around the players so much proved to be a valuable learning experience. “In those days, you spoke cricket. Can you imagine sitting next to Marshall, Rawson, and Rice? Sometimes we would leave the ground at 19:00 or 20:00, having listened to these guys’ stories until it was late.”

After some time, Graham Ford asked Andrew if he would be interested in working as a full-time trainer out of the Natal Cricket Union’s indoor centre. He said a gym would be added on the side. Andrew agreed to it and turned his sole focus to cricket.

It was an interesting time. Under the leadership of Malcolm Marshall, the approach of the Natal team was changing. Some players, like Marshall, were full-time professionals, while others, like Peter Rawson, Mark Logan and Errol Stewart, held down jobs, which meant different practices times for different players. In addition, a number of Natal players had to travel from the Pietermaritzburg daily to attend practices. There was a period of adjustment needed.

The Dolphins celebrate winning the Standard Bank One Day Cup in 1996/97.

It also became a valuable learning environment for Andrew. He said: “Fordie would go and throw and he would, for example, say Jonty was coming in for a net and I would throw to him. I had quite a strong arm from playing waterpolo and I got the nickname ‘Wayward Wally’. Every time Fordie would coach I watched and listened. It got to the stage where guys would ask me to throw to them when Fordie was busy. I got to teach myself about the game.

“I had guys in those days, like Jonty and Andrew Hudson, while Lance [Klusener] and Polly were coming through. Often when I threw to them, those guys knew their games, so they taught me what to look for. I learned and developed.”

In 1998, Graham Ford joined the Proteas as an assistant coach to Bob Woolmer. When he did that, he asked Andrew to take over the Cricket Academy at Kingsmead. Andrew subsequently took charge there and started coaching the under-19 team, while staying involved with the senior side. During that period he also built up a particularly strong relationship with another former DHS boy, Lance Klusener, and Jonty Rhodes.

Andrew hanging out with Lance Klusener. He built up a particularly close relationship with the DHS Old Boy during his time with Natal cricket.

“They would have no one else coach them, no one else throw to them other than me,” Andrew said. “I spent a lot of time with Lance prior to the 1999 Cricket World Cup, and also with Jonty.”

Klusener, of course, went on to be named Player of the Tournament at the Cricket World Cup after a string of devastating match-winning performances. The South African challenge, sadly, ended in the semi-finals when, after playing to a thrilling tie against Australia, they were eliminated from the tournament.

“Lance and Jonty taught me a lot,” Andrew said. “I would get a phone call from Lance from the West Indies, for example, and he would ask if I had watched him bat and how did he do. If I didn’t watch, he would shit all over me.

Take a 5-star break from life in the fast lane. Contact Fordoun CEO and former Michaelhouse rugby star Richard Bates for your well-earned break. https://www.fordoun.com/

“Through the course of time, people like [DHS old boy] Hashim Amla came through the system. [DHS old boy] Imraan Khan came through the system, and people like Mark Bruyns, Doug Watson, and [Zimbabwe international all-rounder] Neil Johnson. Natal was a formidable team. It was great to be involved with them.”

Change is inevitable, though, and one day, in 2003, it announced itself. “A letter got slipped under my door to say thank you very much, but your services are no longer required. I was a bit upset and I tried to fight it, but I was fighting a losing battle.”

Resetting, that same year, in March, he set up the Shedders Cricket Academy. It has been in operation ever since. Andrew explained: “I started at DPHS. From there I moved and coached from home. Then I ended up at Northwood for 10 years.” There he served the school as a professional coach, assisting all teams. He was subsequently appointed the Director of Cricket and also coached the 1st team.

Gareth Orr (right) was one of the first boys Andrew coached when he started his cricket academy in 2003. Gareth went to Maritzburg College, played for KZN Inland, and then went to study at the University of Pretoria. When he decided to start playing cricket again in 2020, he once more turned to Andrew for coaching.

After leaving Northwood, he moved to DHS. The Shedders Cricket Academy now operates out of DHS and, coming full circle, DPHS, where it all began.

Reflecting on his manner of work, his coaching style, and what he has to offer as a coach, Andrew said: “One advantage I’ve always felt I had was that I had played international sport and I knew the pressures of playing at that level.

“I feel a lot of my coaching is focused on motivation, encouragement, and positive reinforcement. Cricket is one of those sports where it is so technical that you can find a fault with every shot or ball. I try to avoid that and make it a lot more positive.”

Interestingly, his coaching has also impacted on some prominent England internationals. Craig Roy, had played provincial and international waterpolo with Andrew, so when Craig’s son, Jason, was starting to make his mark with Surrey he arranged for him to come out to South Africa to spend six weeks with Andrew to work on his game. It wasn’t the last time Jason, who went on to earn his England colours as a hard-hitting top order batsman, sought out his coaching.

Andrew has worked closely with England international Jason Roy, the son of his former waterpolo team-mate Craig Roy.

Kevin Pietersen, too, when he was in the wilderness in Natal cricket, before his move to England where he became a mainstay of the national side, turned to Andrew for coaching and that resulted in many hours spent at Kingsmead with the pair working on Kevin’s game.

Andrew also spent time coaching future England one-day international captain Eoin Morgan, and that led to one of the few regrets of his coaching career. He said: “I worked a little bit with Eoin when he came out and spent six months at Saint Henry’s as a schoolboy. It was at a time that [future Proteas’ assistant coach] Adrian Birrell was just finishing off as the Ireland coach and Ireland were trying to persuade Eoin Morgan to keep his Irish citizenship and play for them. I worked with him and I got offered a job at Malahide Cricket Club, which is now a test venue for Ireland cricket. You look back and wonder what if I had taken the job?”

Cricket, though, did take him abroad to the hot bed of India and it almost resulted in a position in the lucrative Indian Premier League (IPL). “I got quite involved in the Indian Cricket League (ICL), which was the one that got banned,” he said. “I was coaching in that league and I had a phone call from [the first chairman and commissioner of the IPL] Lalit Modi prior to the IPL starting, but we were already down the road with the ICL. You look at those things [and wonder], but I have no regrets.”

One of the true greats of the game, Sri Lankan batsman Kumar Sangakkara, with Andrew at the 2016 Masters Champions League.

Nowadays, as CEO of the DHS Foundation, Andrew has an office on the school’s grounds and the Shedders Cricket Academy makes use of the High Performance Cricket Centre, coaching in and around school practices. He is no longer involved in the day-to-day running of the Academy, but takes the occasional session. He has three coaches in his employ.

Still, coaching provides him with a sense of satisfaction. “It is a lot about motivation and encouragement, about boys enjoying themselves and the time they spend with me.

“I’m very happy to coach a boy that plays in the under-11 D team and the very next session I will coach a provincial player. It’s about adapting, and I get as much enjoyment out of coaching the under-11 D players as I do out of coaching first team or provincial players,” he commented.

Pivotal Talent’s Online SubjectChoice (Grade 9s) and CareerGuide (Grade 10s, 11s and 12s) solutions replaces uncertainty with accuracy in directing your children to make full use of their potential. Check out www.careerguidesolution.co.za

He feels encouraged and is so positive by what is currently happening at DHS. “DHS is most definitely on the up and, crucially, DHS is gaining the confidence of its Old Boys again. Boys and parents alike are now choosing DHS, where not too long ago they might not have even considered it as an option. Our academic structures are constantly improving, and our sport is again starting to compete at top levels.”

“There are so many good things that are happening at DHS, for example, the introduction of Cambridge and the Nonpareil extension programme,” Andrew said.

“Under the school’s leadership of Tony Pinheiro and his staff, it is so pleasing to see where his team has taken the school to in such a short period of time. I am not just standing and preaching it, it is genuinely happening. The school is constantly evolving and looking for ways to improve. We all market our school with passion. We are getting there. Our numbers are up, our boarding establishment is full and as mentioned earlier, DHS now offers the Cambridge system.”

While Andrew now focuses on his work with The DHS Foundation and his passion for DHS, the legacy of Shedders Cricket Academy continues in the capable hands of his son Ross (seen here on the occasion of his last match for the DHS 1st XI) and his loyal and dedicated coaches who, overseen by Andrew, continue to coach cricket with the same coaching principles of passion, hard work and positive coaching mentality.

From Westville to the world, leading tennis commentator Robbie Koenig

9 June 2020 – Born and raised in Westville, Robbie Koenig turned a love for tennis into a pro career and when that was over he took his connection with the sport to even greater heights by becoming one of the world’s leading tennis commentators. KZN10.com’s Brad Morgan chatted with him recently.

As a young sportsman at Berea West Senior Primary school, Robbie also showed talent in cricket and was good enough to represent Natal B as “a bit of an all-rounder, jack-of-all-trades, but master of none.” But tennis was the sport he excelled in and when he moved on to Westville Boys’ High, which his brother had also attended, he became part of a remarkable hotbed of talent.

“Westville was number one in the country,” Robbie recalled. “I’ll tell you the team that won the national schools championships. It was the top four players in the team, playing singles and doubles. It was me; Ellis Ferreira, a Grand Slam champion in doubles; Roger Mills, who went on to play College tennis in the states; and Kirk Haygarth, who went on to play on the Tour as well. Myles Wakefield might have been there already. Maybe it was six guys. Myles went on to a good career on the Tour too.

“Westville in those days and Natal, in particular, were unbelievable. I remember we played one of the Joburg schools in Joburg, and the winners got a trip overseas.

“We had such a rich history. Going back a number of years, there were people like Royce Deppe, Grant Adams, and Bruce Griffith.”

The Westville 1st tennis team of 1988 included three players who would go on to play the game professionally: Robbie Koenig, Myles Wakefield and Kirk Haygarth.

“School was just a happy place for me,” he said. “The environment at Westville was just so positive. You had people like [future Headmaster] Trevor Hall, who was the Deputy Head when I was there. He taught me some accounting. Again, an ultra-positive guy, so supportive of the tennis environment, because he was a former tennis player.

“Overall, my over-riding feeling was that it provided such a supportive framework. Whether you were excelling in academics or sport, you were given the same credit. Doing well at tennis, I was made to feel as good as the guy who was dux of the school. It is testimony to the teachers that were there, so many good people. They knew people skills.”

From an early age, Robbie was coached by John Yuill, who had ranked as high as 52nd in singles in the world during his career. “He was far and away the most instrumental influence in my career,” Robbie acknowledged.” John’s outstanding ability as an exponent of the serve and volley game would later help Robbie become a four-time Grand Slam semi-finalist, three times in mixed doubles and once in men’s doubles.

An incredibly talented squad of youngsters until the tutelage of Yuill also helped Robbie develop his game further. Then there was his uncle Guy (Gaetan) Koenig, who had represented South Africa in the Davis Cup. He served as an inspiration.

Get a firmer grip on your possessions with KZN’s Titan Technologies. https://www.titantech.co.za/

In club tennis, he learnt lessons playing mixed doubles that would later prove invaluable. “I remember playing mixed league on the weekends at Westville Tennis Club when I was 15, 16 years old. Ladies of a certain age, around 45, didn’t move that well, so I had to learn how to cover 90 percent of the tennis court,” he said.

“You become unbelievably good at reading so much more. You learn how to help your partner and close down the gaps on the doubles court, things that a lot of other people maybe don’t learn. Playing much more structured league, like men’s doubles, you don’t have to worry about your other half of the court because that person has got it covered.

“I’ll tell you what, Barbie Walker made me do a lot of covering when I was playing at Westville. I probably have got to thank her for a couple of my mixed doubles semi-finals at the Grand Slams as a result of that.”

Anyone who has heard Robbie commentating on tennis will know of him as a tremendously enthusiastic and positive person. Those traits come from his dad, he explained: “My dad was one of the most outgoing, positive people to be around. I think I inherited a lot of that from him, a love for life and my enthusiasm. People like to be around me because of my positive energy. I definitely got that from him.”

Wimbledon 2017: Robbie Koenig with one of his former doubles’ partners, John-Laffnie de Jager; Wayne Ferreira, who was part of the same generation of young South African tennis talent; and David Friedland.

As a rising talent in a generation of top South African youngsters, Robbie received offers from Pepperdine University and the University of Miami, but a decision by Tennis South Africa to establish an Elite Squad to go along with the previously formed Super Squad, which included players like Wayne Ferreira and Marcos Ondruska, meant Robbie chose to forgo the university route.

The support from the national federation lasted 18 months and helped get him into the pro ranks. Seeing players like Ferreira and Ondruska (a player he regularly beat as a junior) perform well at Wimbledon and the French Open respectively, also provided inspiration that he could make it as a professional.

Reaching that level, though, took a lot of hard work because, Robbie admitted, he was not one of the most talented of the young South Africans. Kevin Ullyett, who became a three-time Grand Slam champion in doubles, described him as a never-say-die, fight-for-every point type of player on court, which Robbie appreciated.

“That’s awesome to hear that coming from a guy who had the career he had. But I needed to be the toughest fighter because I didn’t have the talent he had. I’ve always had a great work ethic and good discipline, but that was because I didn’t have the talent of guys like Ellis Ferreira and Ully, especially. He was unbelievably talented.”

When it comes to planning your next school sports tour look no further than former Hilton College first XI captain Craig Goodenough who’s been there, seen the movie and bought the T-shirt factory.

On the ATP Tour, Robbie enjoyed some success in singles, but quite early on in his career he had to deal with knee problems. As a smaller player – five-foot eight and no more than 70 kilograms at his heaviest – his body was not prepared for the demands of life as a pro. He had to endure two knee operations, which sidelined him for 13 months.

“I came back after that a lot smarter,” he said. “I used to do a lot more bike work, a lot more non-impact stuff. I wish I had known that when I was 16.

He also decided to focus on doubles which, with the benefit of hindsight, he wished he had done a little earlier in his career. John Yuill’s coaching and days spent playing mixed doubles at the Westville Tennis Club were about to pay off. The fact that a lot of South African tennis was played at altitude in Johannesburg was another plus, he added.

“Many of us grew up playing or competing at high altitude, which almost made it a necessity to be able to serve and volley. That became an important part of your game and you learnt that skill from a young age. Obviously that translates so well onto the doubles tour.”

Furthermore, in doubles one had the advantage of being able to share the load with a partner, whether in victory or defeat, and the switch proved to be an easy one.

The world-renowned tennis commentator with his former doubles’ partner and former South African Davis Cup captain John-Laffnie de Jager.

“When I teamed up with John-Laffnie (de Jager), I couldn’t believe how easily I made the transition to top level doubles. It came very quickly. The first big tournament we played together was the US Open. We qualified there and made the quarter-finals.

“That was my decision to give up on my singles, really, because in one week at the US Open I made more money than I had made in the previous eight months playing singles.”

Robbie went on to make four Grand Slam semi-finals in his career, one in men’s doubles and the other three in mixed doubles.

Early on, there was a tendency to look to partner with South Africans. Later on, it was about finding players whose games melded with his, which created opportunities to win, Robbie said.

“I always felt if I had a decent partner alongside me I could do some serious damage. For a while, I think in some of the partnerships I had I was the slightly better player, but I needed someone who was better than me. When I played with guys who were better than me, I found it easy to win.”

When the match is tight and every run counts, you can count of Clox Scoreboards of KZN. http://clox.co.za/

Robbie achieved his biggest successes in mixed doubles, teaming up with the Belgian, Els Callens. He remembered teaming up with Annabel Ellwood, an Australian, and playing Els and her South African partner Chris Haggard at Wimbledon one year. They won, but he thought to himself that he and Els would make a good team.

“I bugged her for about a year or two [to play with me]. At this stage she must have been a top 20, if not top 10, player in women’s doubles. Eventually, she said ‘Okay, Robbie, let’s play’.

“It was easy to win with her. We beat some good teams. I remember beating Martina Navratilova and Leander Paes at the US Open. We made the semis there, the semis in Oz, the semis at Wimbledon in mixed. I wish she had stuck around a bit longer, or I had got hold of her a little earlier, because her game fitted perfectly with mine.”

One of his most memorable matches was the aforementioned quarterfinal with John-Laffnie de Jager at the US Open because the victory made a telling difference in his life.

“In the quarterfinals, we played Piet Norval and Neil Broad. They were top dogs at the time. The difference between losing in the quarters and losing in the semis was that the prize money had started to double by then.

“My wife was pregnant and I knew if we won this quarterfinal match and made it to the semis of the US Open we would have more than enough cash to put down a substantial deposit on my place in London. I remember being pretty nervous going into the match.

It was also played before a clash between Andre Agassi and Karol Kucera, which had to be completed, with their contest locked at two sets-all on Louis Armstrong Stadium.

“They always put a match before a match that needs to be completed,” Robbie explained. “We walk into the stadium, 8 000 people, a full house! They weren’t there to see us, they were there to see the end of the Agassi match, but everybody wanted to get there early and make sure they had a seat.

“We played a really good match in a hostile environment. We ended up winning it. It was a great match, we played unbelievably well and ran away with it in the end [winning 5-7, 6-4, 6-2].

“That was one of the coolest matches I ever played because I remember the relief when we were winning, thinking I’m going to buy that apartment in London now.

“It carried so much significance, with my wife being pregnant and now we were going to move in there. I could finally afford my own place, because we had been sharing houses in London with other people. I think from a significance point of view, making my first semi-finals at a major, it was big at the time. Obviously winning titles was big, but that’s the one that sticks in my mind a lot.”

Halfway through his final season on tour, he turned his focus to coaching. Mahesh Bhupathi, then ranked number one in doubles in the world, asked him to be his doubles’ coach and Wesley Moodie asked him to be his singles’ coach. “Basically, I had two people in my stable, so I could retire from tennis, knowing that I had a gig.”

The timing was good. Robbie had endured a frustrating time with the chopping and changing of his doubles’ partners. He had partnered with Thomas Johannson, the Australian Open doubles’ champion, but fate stepped in to bring about a change his plan when Johannson suffered an injury from a mishit ball, which struck him in an eye and put him out of tennis for half a year.

“That would have been my doubles partner, which left me without anybody to get into the events with. It’s amazing how fate turned out. I would have been relying on Thomas to get into tournaments and the next thing you know the guy is injured for the next six months. Who knows how the chain of events thereafter would have unfolded,” Robbie said.

Fate intervened again shortly after that when Robbie had a serendipitous meeting. “I was living in the UK. I’ve got an apartment just across the road from Wimbledon. It just happened that the guy two driveways up from me was a guy named Jason Goodall.

Robbie and Jason Goodall just before commentating on the Masters 1000 final in Toronto in 2014 between Jo-Wilfried Tsonga and Roger Federer.

“I am walking to Southfields Tube Station, Jason is walking back. We meet each other at the corner. We were pushing our prams and I was with my wife and kid. Jason and I hadn’t seen each other for a while. I knew him vaguely.

“He stops me and asks me ‘Hey Robbie, how is it going? Long time, no see. What are you doing here?’ He said he lived just up the road. I said me too. He asked me what I was doing and I told him I was coaching Mahesh and Wesley. I asked him what he was doing and he said he was working for a company, ATP Media, and he was doing some commentary on the Masters 1000 events.

“I asked who he did it with and he said John Barrett (a Wimbledon commentator for almost three decades). He asked if it was something I would ever be interested in doing. I said not really. I said I had a good coaching gig. He said ‘If you ever want to get into it, or try it out, you’re going to be at these tournaments anyway, here’s my number. Get in touch if you want to give it a go.”

Later, at tournaments in Indian Wells and Miami, Robbie realised why Jason had invited him to give commentary a go. “At that stage there were only three commentators. There were the two of them and there was this guy from the States and the workload was insane.” And John Barrett, then about 80 years of age, was about to retire.

In Indian Wells, after finishing training one day, Robbie went to see Jason. He helped with commentary for a set or two. “It was fun. I wasn’t looking for a job, but I was very natural. Two days later, the same thing happens. I go in for a set here or there. The same thing happens in Miami and the same thing happens in Hamburg, when that was a Masters 1000 tournament. I would do a couple of sets in a row, but didn’t think anything of it.”

Robbie showing Andrew Rueb, a former doubles’ partner and current coach of the Harvard men’s tennis team, the booth at the ATP World Tour finals in London in 2014.

But then, after Wimbledon, Wesley Moodie decided he no longer wanted to work with Robbie. “Suddenly, I am only getting 50 percent of my income, because I was only working with Mahesh. That’s when I realised how fickle a coach/player relationship could be. You don’t have any contracts. When a guy says he doesn’t want to work with you anymore, you’re kind of left in limbo. It was right after that happened that I thought hang on, this commentating gig might be a nice long-term security thing for me.”

In Cincinnati, Robbie did some more commentary work and was then approached by the Head of Production with an offer for a full time job the following year. After a little back and forth, terms were agreed and the stage was set for the next stage of his career. “The bonus was I going to get paid in pounds and they paid for all your expenses,” Robbie said.

“I started in 2007 in Indian Wells. Those were the early days of ATP Media, the world feed. The first couple of years were brutal, just three commentators working 10 hour days. You basically did two sets on, one set off, the whole day. The beauty about that is that I learnt all the skills very quickly. I learnt how to do colour commentary and I also learnt how to do the lead. If I had joined an international company, like ESPN, I would have only been doing the colour commentary.

“My biggest asset was that I had always had a very good mentality on how to see a tennis match. That was my greatest strength, the ability to analyse a tennis match. I think that came across well to the viewers from early on, and certainly to the guys in the production team. My natural analysis of the match was on point. I was reasonably articulate. I didn’t have a funny accent. I had a nice neutral accent, which was for a worldwide audience, and Jason and I bounced off of each other very well.”

Take a 5-star break from life in the fast lane. Contact Fordoun CEO and former Michaelhouse rugby star Richard Bates for your well-earned break. https://www.fordoun.com/

Since then, it has been a fulfilling journey for the Westville old boy. Last year, he joined Amazon Prime, which has taken over tennis in the United Kingdom from Sky Sports.

“You won’t hear me as much now in South Africa,” he said. “You’ll hear me at the majors, except the French I don’t do. I do the world feed for three of the majors. Now for the ATP 1000s and 500s, all of them I do for Amazon Prime in the UK. They’ve got the men’s and women’s rights now. Last year, they signed a four or five year deal for the ATP rights, and now they’ve got the women on board, so it is all on one platform.”

As a commentator, two matches have stood out as being very significant to Robbie personally: “The 2017 Australian Open final because, remember, Federer was 3-1 down in the fifth, he had just got broken. I put off my microphone and I looked at my co-commentators and I said ‘I can’t believe it, Nadal’s got him again.

“It looked like Rafa was going on to win it and what happens? Roger wins five straight games to win the match. It was incredible. The drama in that match was off the charts. Roger had just come back from injury and the atmosphere was mind-blowing. That was right up there, if you talk about big matches.

As a commentator, calling the 2017 Australian Open final between two of the all-time greats, Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal, was an incredible experience for Robbie Koenig as he witnessed the Swiss maestro capture his 18th Grand Slam title five years after his 17th. (Photo: YouTube)

“The other one, I did for radio at Wimbledon was when Andy Murray won Wimbledon for the first time. He beat Novak Djokovic in the final. It had special meaning for me.

“I first came across Andy when he was 15 and Chris Haggard and I played doubles against him at Nottingham, which was one of the warm-up tournaments before Wimbledon. We played this wildcard pair, and he was half of that team, and I could not believe how well this kid returned serve. Chris was a lefty and had a nasty lefty serve on grass. In the first five games, this kid was incredible. If I crossed, he went down my line. If I didn’t cross, he returned it on Chris’ shoelaces. We were staring at him, trying to intimidate him.

“Anyway, we ended up playing everything to his partner, Martin Lee, who we both knew well. He eventually crumbled. This 15-year-old kid, Andy Murray, was as steely as could be.

“After the match, he walked over to his mom and his mom put her arm around him. I was speaking to my family and I walked over to them. I said ‘this kid of yours, if you’re the mother, he’s fantastic, an unbelievable talent’. Of course, it was Judy [Murray]. She said ‘Thanks very much, Robbie’. I said ‘If he just keeps it up, this kid is going to be a proper talent and I hope he can go on to do good things because he’s a proper player.’ Andy was standing there.”

A sticky wicket makes for messy backyard cricket. Take action before it’s too late. www.midlandssepticservices.co.za

Robbie kept following Andy Murray’s career and that included seeing him make a couple of Grand Slam finals before being beaten at the final hurdle each time.